Social Values In A Time of Change by Joyce Hylton MBE

Social Values In A Time of Change

Joyce Hylton MBE

Looking back on the years 1947 to 1983, it seems obvious from today’s perspective that the period referred to as “The Southwell Years” was one of dramatic social change in Cayman. One of the sad aspects of that change was the extent to which family life and traditional values deteriorated.

I assume I was asked to contribute this article on social conditions because of my work as Probation and Welfare Officer during part of that era. May I assure everyone that, in putting my thoughts together, I have not referred to any family’s or individual’s confidential records. I have, however, refreshed my memory from a few of the Annual Government Reports of those years, although I must add that I don’t necessarily agree with some comments they contain.

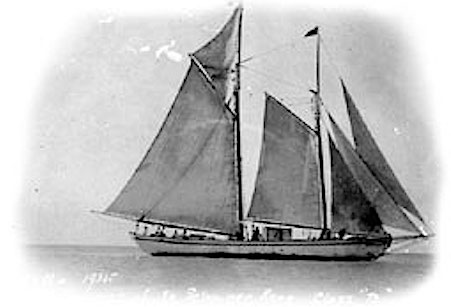

After looking at the situation from many angles, I have come to conclude that social changes came about because of numerous influences. My personal opinion is that Caymanian men going to sea was not a major negative factor. In the beginning, we as a people were being exposed to outside forces at a pace we could absorb. Maybe we did not cope so well later, when the added prosperity associated with tourism and the financial industry brought us so much so quickly.

Government Annual Reports as early as the 1930s mention the “remitted wages” of Caymanian seamen as being an important part of commerce by helping to balance the excess of imports over exports. So men going to sea was not suddenly a new thing in 1947. Absent husbands and fathers were a fact of life and I think we dealt with that reality, for the most part, as well as could be expected. There was, after all, both emotional and financial security in the knowledge that the men would eventually return and their families were provided for meanwhile. Divorce was not common. Few households were forsaken or neglected. In fact, I know from my work with maintenance and affiliation that the men who shirked their responsibilities and were taken to court were those living and working here.

The great majority of men all along were sending money back to support their families. You credited your purchases at the little grocery stores and shops and then you paid when the allotment came. It is true that some people spent their money foolishly sometimes. I remember when corn flakes became popular. Some people had to have corn flakes every day because they were imported. Home made porridge wasn’t good enough anymore. Later, restaurant “fast food” was in style. Some people on poor relief were buying Kentucky Fried Chicken regularly. I had to show them that buying rice and uncooked chicken would make their money stretch further.

My appointment as Probation Officer came in 1963. The post was established originally to deal with juvenile offenders after others in the community joined in my concern for young persons being dealt with in a public court the same as adults. Welfare work was added to the post a short time later because a child’s problem was often rooted in a family problem. Mrs. Gay Jackson joined me in 1967.

Here is a quote from the 1961-65 Government Report: “The majority of the Islands’ juvenile offenders are the victims of broken homes or parental neglect, but some of the teenage boys are from respectable homes where, due to absence of their fathers at sea or to parental weakness, they are not subjected to a man’s discipline after school hours and during the school holidays.”

I do not blame men at sea for children’s delinquency. In fact, the report goes on to say that, for 1965, there was a total of 13 juvenile cases; nine of them involved youngsters between 14 and 17 years of age. Other youngsters also came to my attention because we were trying to deal with them in the preventive stage.

There were a lot of home visits and talks with the children, most of whom seemed to appreciate the extra attention and interest in how they were doing. In those days at least one parent was home. In later years, we would find only a grandparent at home because both parents were out working. Later still, there was no one at home during the day at all. Parents started shifting responsibility for their children’s training to the schools and Sunday school because they were so busy out making the almighty dollar.

One area where we did notice the shortage of manpower from early on was in scouting. For the Cubs, we had no problem. But when it came time for them to move up, we could hardly do it because there were few men to lead the Boy Scouts.

The numbers of young people did continue to grow after the Juvenile Court came into being: 20 cases in 1966; 34 in 1967; 25 in 1968; 41 in 1969; 53 in 1970. But Grand Cayman’s population was growing, too, and we dealt with children from various backgrounds, including those whose parents came from Jamaica and Central America.

The Government Report for 1961-65 speaks of Caymanians as being a God-fearing and independent people. It states that, “only a few individual Caymanians believe that the world owes them a living.” That was true. In 1950nMis Francis Bodden, secretary to the Commissioner, administered government funds for poor relief and recipients received a few shillings. When our little Probations Department became “Probation and Welfare” I was ashamed of the pittance Government gave me to give out. I knew I was dealing with a proud people. When I had worked in Jamaica I could go into the hills and give families used clothing I had collected. I couldn’t do that in Cayman. Here it took tact and an indirect approach. I would receive some very nice items from the English people and then go to someone I thought could use them. I would ask: “Do you know anyone who would like these clothes?” One lady answered me, “Well, Miss Joyce, you didn’t know I need them?’ I said no and she took them happily.

The years 1966-70 are described in the Government Report as a period of “continuous rapid growth on nearly all fronts” which “led inevitably to stress and strain both in the social life on the Islands and on the machinery of government.” The report speaks of full employment and fast-growing prosperity, with 500 new companies established here in 1970 alone. Why was it that I began to find the need for so much financial assistance when we were supposed to be in so much prosperity? Were some people left behind? Did we not have our priorities right? I remember when television became the rage, there were some people who would rather buy a TV set and have nothing to eat. I once saw some children at a tape club. I asked the owner if the youngsters had a TV at home. “Yes, ma’am,” he assured me. There I was, authorizing poor relief for the family from government funds. I marched down to their house and explained in no uncertain terms what the money was meant for: it certainly did not include TV and tapes.

Cayman use to be a place of caring and sharing. There was no moaning if you didn’t have something. A child with a bicycle, for example, would take pleasure in letting his friends ride it. The child without a bicycle knew his friend would share. It was the same with other things, including food. No one in Cayman starved and there were no beggars. Nowadays some people consider themselves poor if they can’t “keep up with the Joneses”.

Sometimes applications would come in for financial assistance, but when I would investigate I would realize welfare was not needed. Several cases involved elderly parents with property but no steady income. The adult children would request help for the parent; they had to be told if government took over his/her care, then government would take over his property. In some instances we could provide free medical if the children kept the parent at home and looked after his or her other needs. They would understand and everything would work out fine.

In one case, our department had to pay someone to put drops in the eyes of an elderly lady; she had family living around her, but they were all off to work each day.

Mrs. Jackson and I worked as a team until her promotion in 1974. A young American, Mr. Steve Smith, then joined me and is still there.

We did have some short-term problems over the years. At one stage I had to go to the dock to stop boys as young as 12 from working when they should have in school. They were helping unload ships. I had to read the law to the adults in charge. Truancy was not a problem for long, although it was mentioned in the government report for 1973. High school students were leaving school at the lunch break. They would go into the bush, change clothes and head for town. I had to be there nearly every noon. The problem was solved through cooperation with parents, the school and police; officers were quick to let me know if they saw someone on the street who shouldn’t have been. In the late 1970s the bright lights and music meant to attract tourists were also attracting underage students. By that time we had another expat probation officer, Ms. Pam Davey, and she made it her business to go to the hotel bars and remove youngsters trying to obtain drink under false pretences.

I retired from government service in 1983. Since then, the department and its work have increased tremendously as Cayman continues to develop.